Working at the intersection of objects, memory, and human experience.

I am an artist and designer working with historical materials, found objects, and visual systems to explore how people assign meaning to things—and how objects continue to accompany us across time.

My practice is rooted in close looking and care for material culture. I work with historical artifacts, found objects, and handmade materials—postcards, photographs, wood, paintings, and everyday items that have endured beyond their original context.

Across both my art and design work, I am interested in how objects function as witnesses: how they document human presence, carry emotion, and accumulate meaning over time. I’m drawn to items that were shaped by human hands and held long enough to matter—objects that invite empathy, attention, and reflection.

Through re-contextualization, preservation, and visual interpretation, I aim to create environments and experiences that slow people down, encourage curiosity, and support meaningful connection.

CREATED

My art practice often begins with found or archival materials—objects that have lost their original context but not their humanity. I work as a temporary steward, holding these items for a time, learning from them, and allowing them to continue their journey.

With this series, I’m exploring the idea of something not-from-your-body being added to the body. The invasive and intrusive nature of surgery.

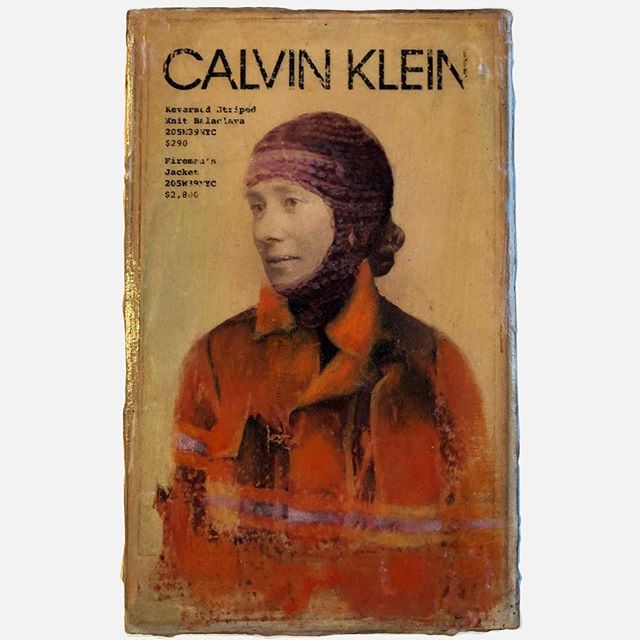

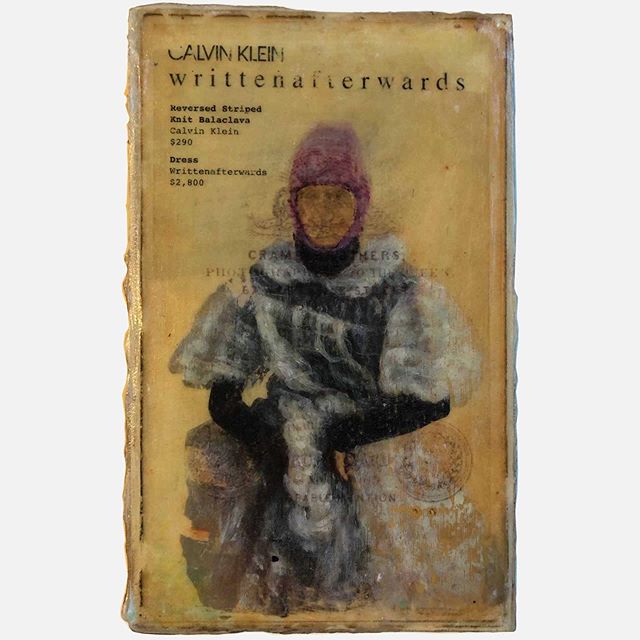

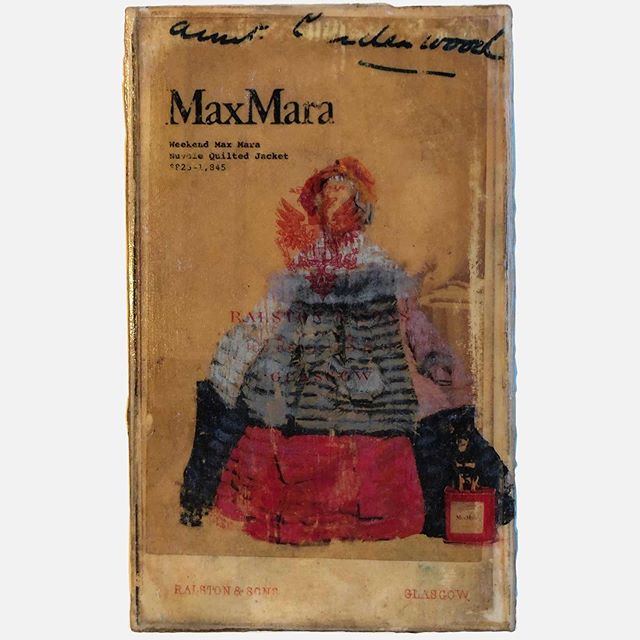

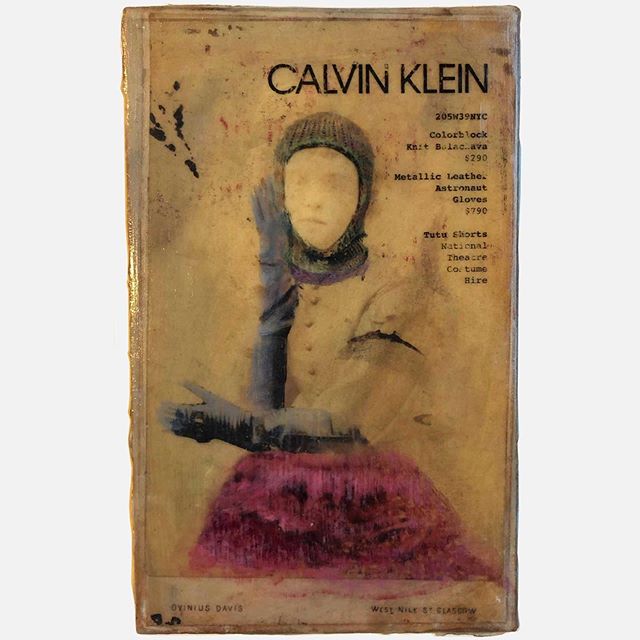

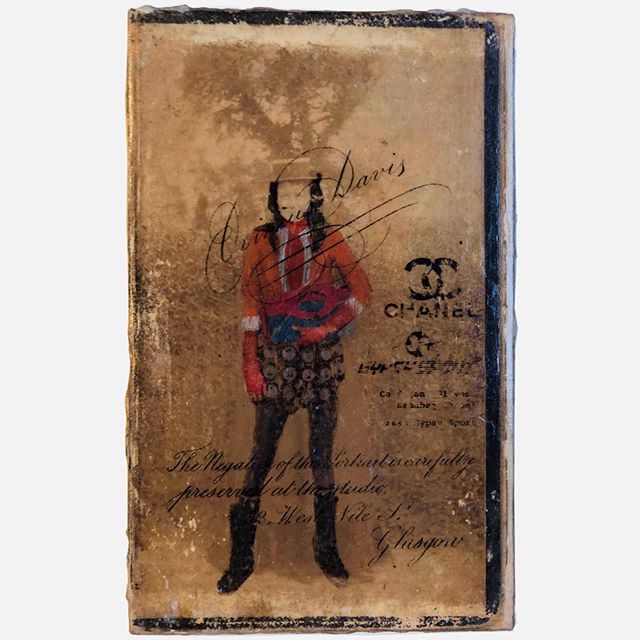

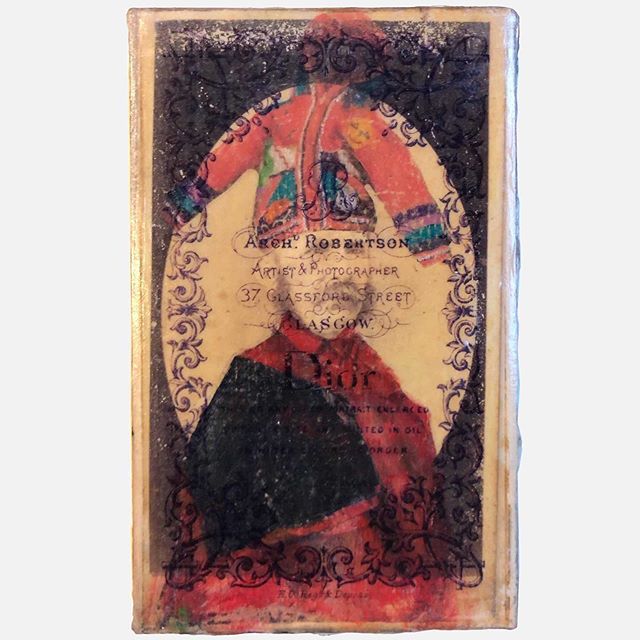

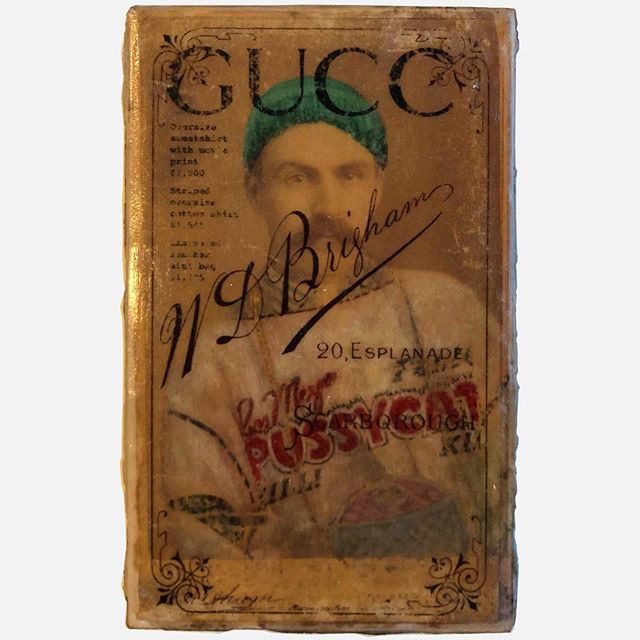

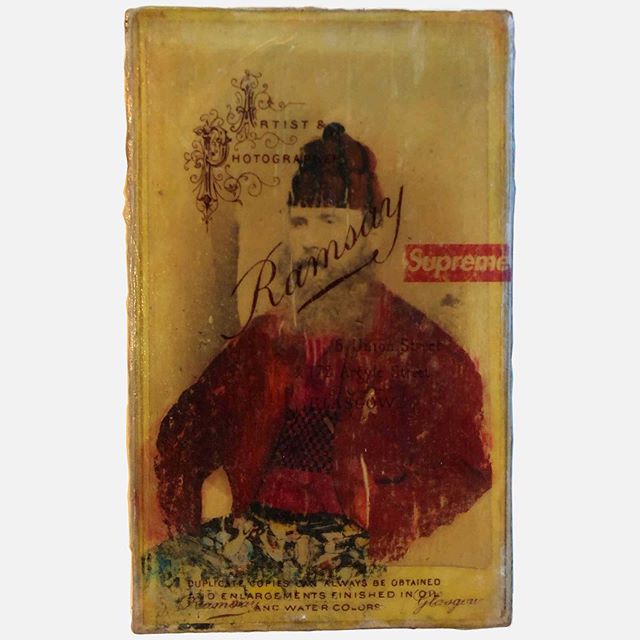

Combining 19th century carte-de-visites portraits with contemporary haute couture fashion, this series explores mash-ups embodying the evolution of photography as social media and social currency.

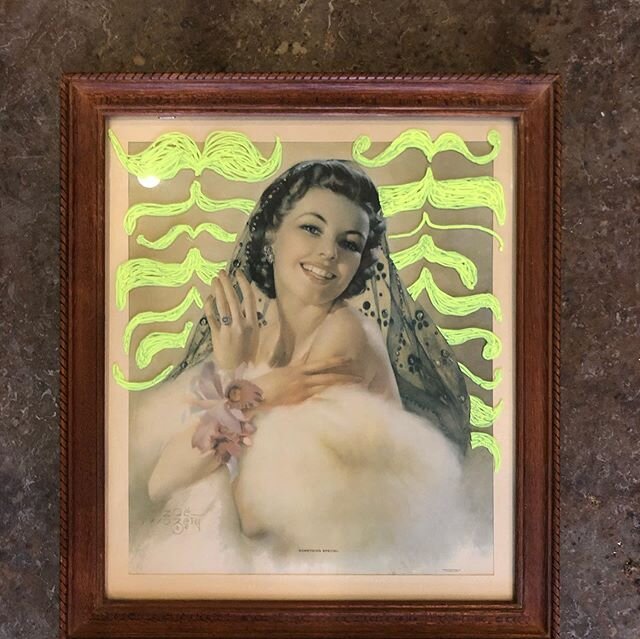

This series explores the idea of herds on modified existing framed prints.

All of these pieces use antique print materials, with collaged elements on top, including transfers of historical photos or rubber stamps, to give an alternate context to the original.

These photos document existence in another time and place. Not the big events or important people, but the mundane and everyday. I found the photos in this series in an unlabelled folder at the provincial archives, and the seemingly random nature of the subjects drew me to them.

These boxes are like little devotional objects for characters. The exteriors show their outer appearances, and the interiors delve deeper into their characters, revealing their traits and secrets. Each character has an element associcated with it, as well as a color. And the edges of each wooden base has a pattern unique to each character.

COLLECTED

I collect and live with handmade objects and artworks by unknown or lesser-known makers. These objects—wooden toys, pottery, paintings, and domestic artifacts—accompany me now, just as they once accompanied others. They inform my understanding of care, continuity, and the quiet power of material presence.

A quiet prairie barn, painted in Edmonton in 1971 and sold through a local art shop. This small work by Ferdinand Friedl is less about nostalgia than it is about presence — a record of how art circulated, what it depicted, and how everyday landscapes were once brought home and lived with.

A winding path, a quiet cabin, and trees glowing at the edge of winter—signed B. Long, and painted with a calm, deliberate attention that rewards time spent looking.

A quiet mountain lake, painted by someone who lived close enough to return again and again. This mid-century landscape by Reuben Carlson reflects a regional practice rooted in familiarity, observation, and place — not spectacle, but presence.

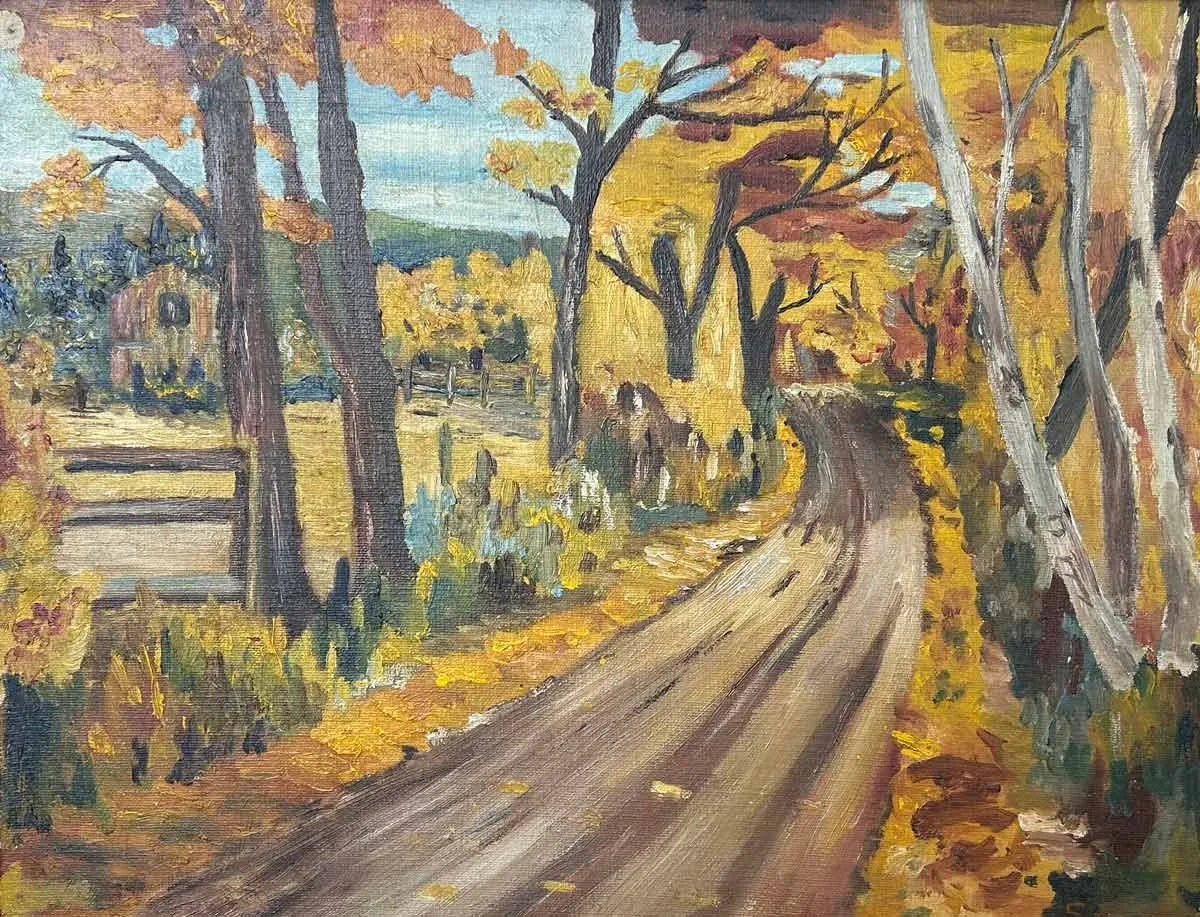

A winding road, autumn light, and a paper trail that refuses to disappear. This 1951 exhibition painting by Stanley C. Riviere reminds us that mid-century Canada quietly celebrated everyday creativity — and that those stories are still worth holding onto.

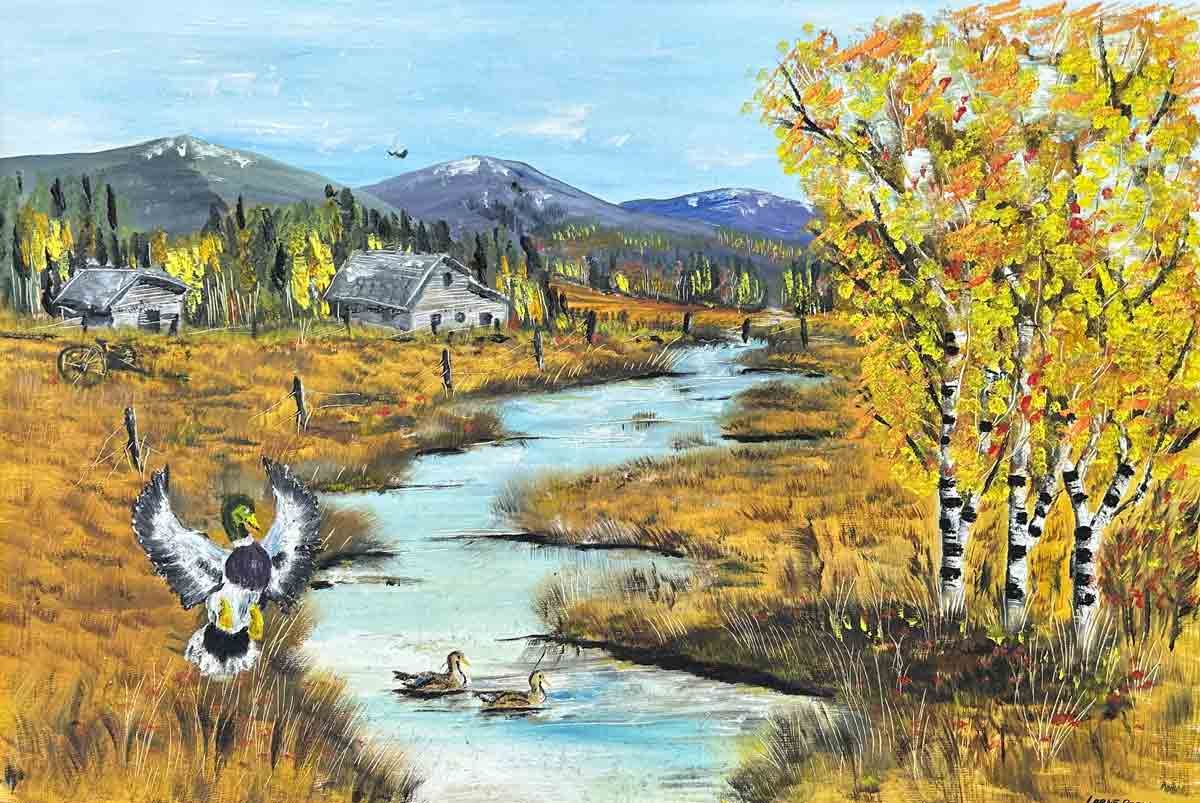

A signed landscape by Lorne Presniak, depicting a rural creek, ducks, and autumn trees. A quietly composed scene preserved without formal record beyond the name on the canvas.

A still life signed Jane Cain, carrying both an artist’s name and a traceable chain of ownership. Quietly domestic, carefully composed, and possibly connected to a Calgary-based woman artist whose work lived outside public record.

Two wood-panel landscapes by E. Robinson, each named and rooted in the Fraser Canyon. Steamboat Rock and Mt. Skihist, painted with weight, texture, and a clear commitment to place.

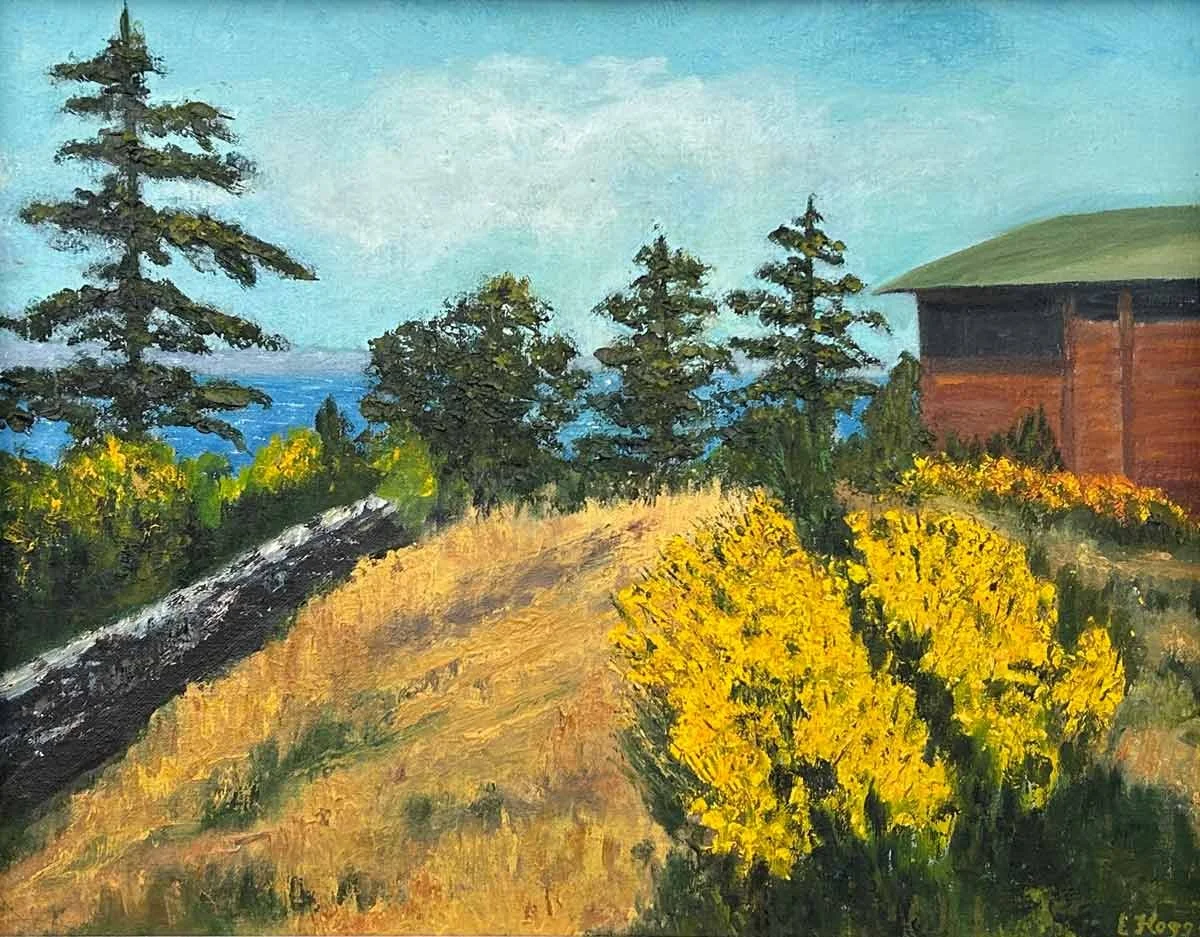

Signed E. Hogg and otherwise undocumented, this modest landscape captures a place known through daily life. A fragment of regional painting history that survives without a name attached to it.

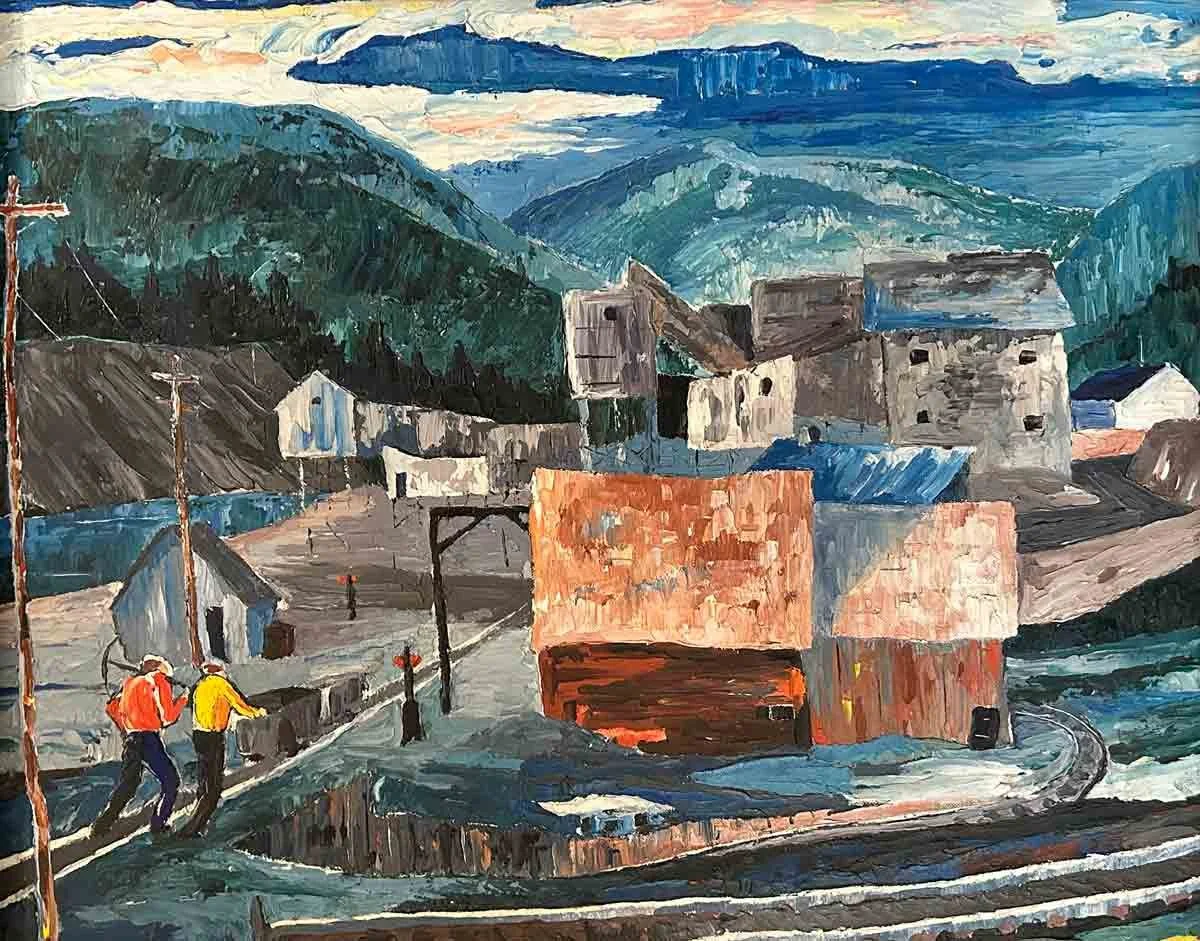

Working life, rendered quietly in paint.

Painted on the same day in 1974, these two works by Alice N. Waldron feel less like standalone pieces and more like pages from a personal record.

I don’t know exactly where this landscape was painted, only that it’s signed H. Belley. A small cabin sits beneath towering rock faces, held in place by paint and memory. I came across it by chance, and kept it because it feels rooted—made by someone who spent time looking.

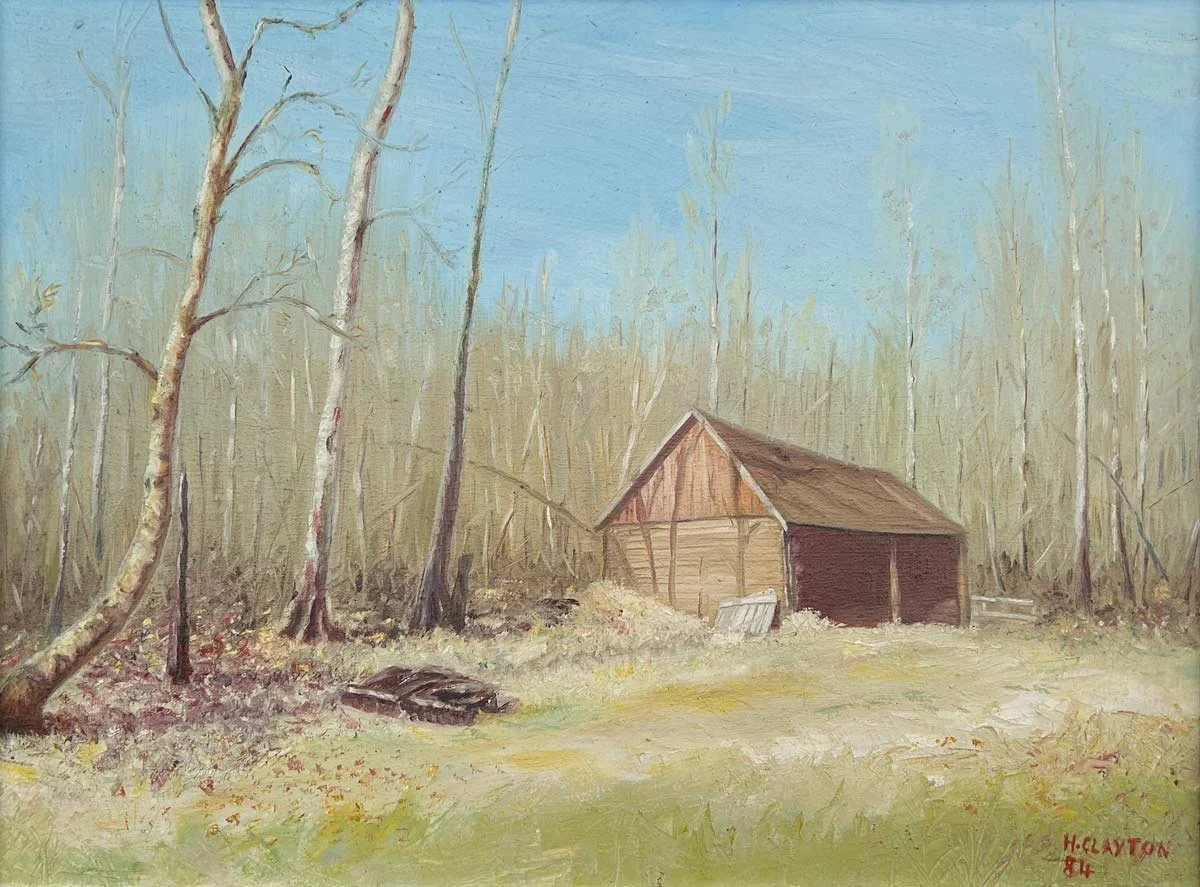

I don’t know much about this painting beyond a signature: H. Clayton. There’s no date, no title—just a small structure at the edge of a clearing, carefully painted and left behind.

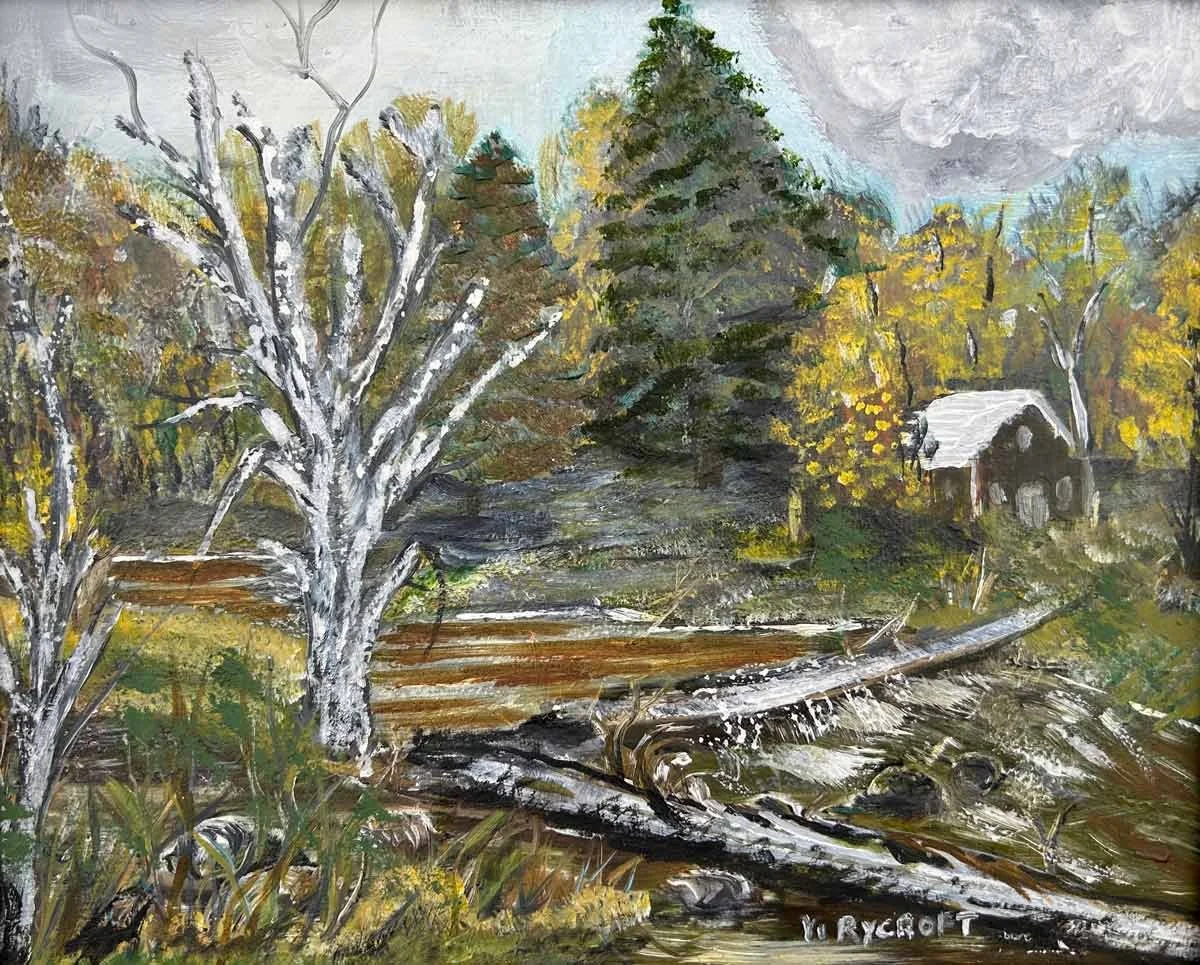

I don’t know much about Violet Rycroft beyond what’s written on the painting itself. Signed and dated 2000, this small oil landscape feels like part of a quiet, ongoing relationship with place—one that didn’t need an audience to exist.

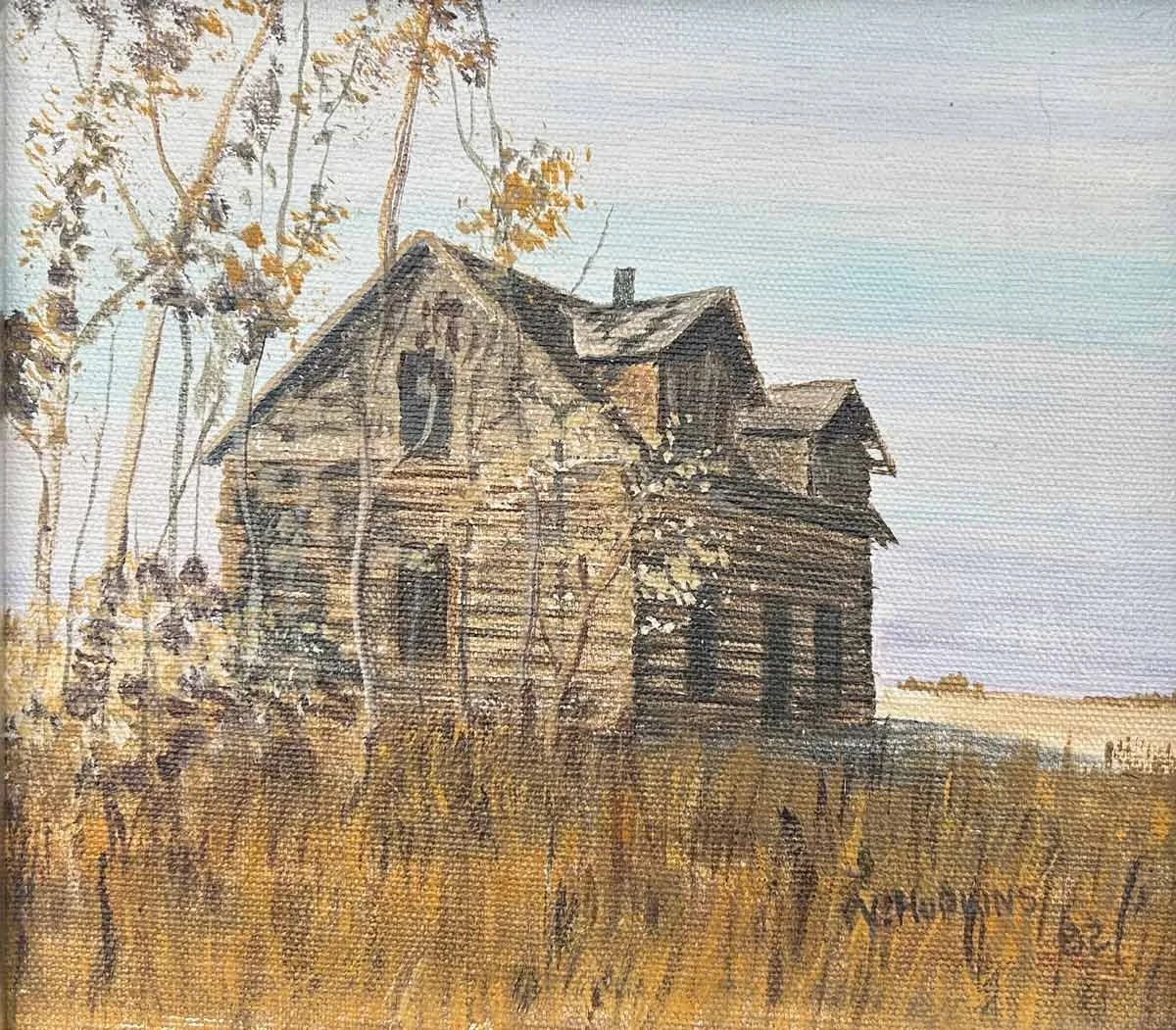

A small acrylic painting signed “V. Hopkins ’82” carries a careful record on its reverse: a farm home’s location, its original builder, and a brief note of where he went after. A Farm Home preserves a place and a life through the quiet authority of handwritten memory.

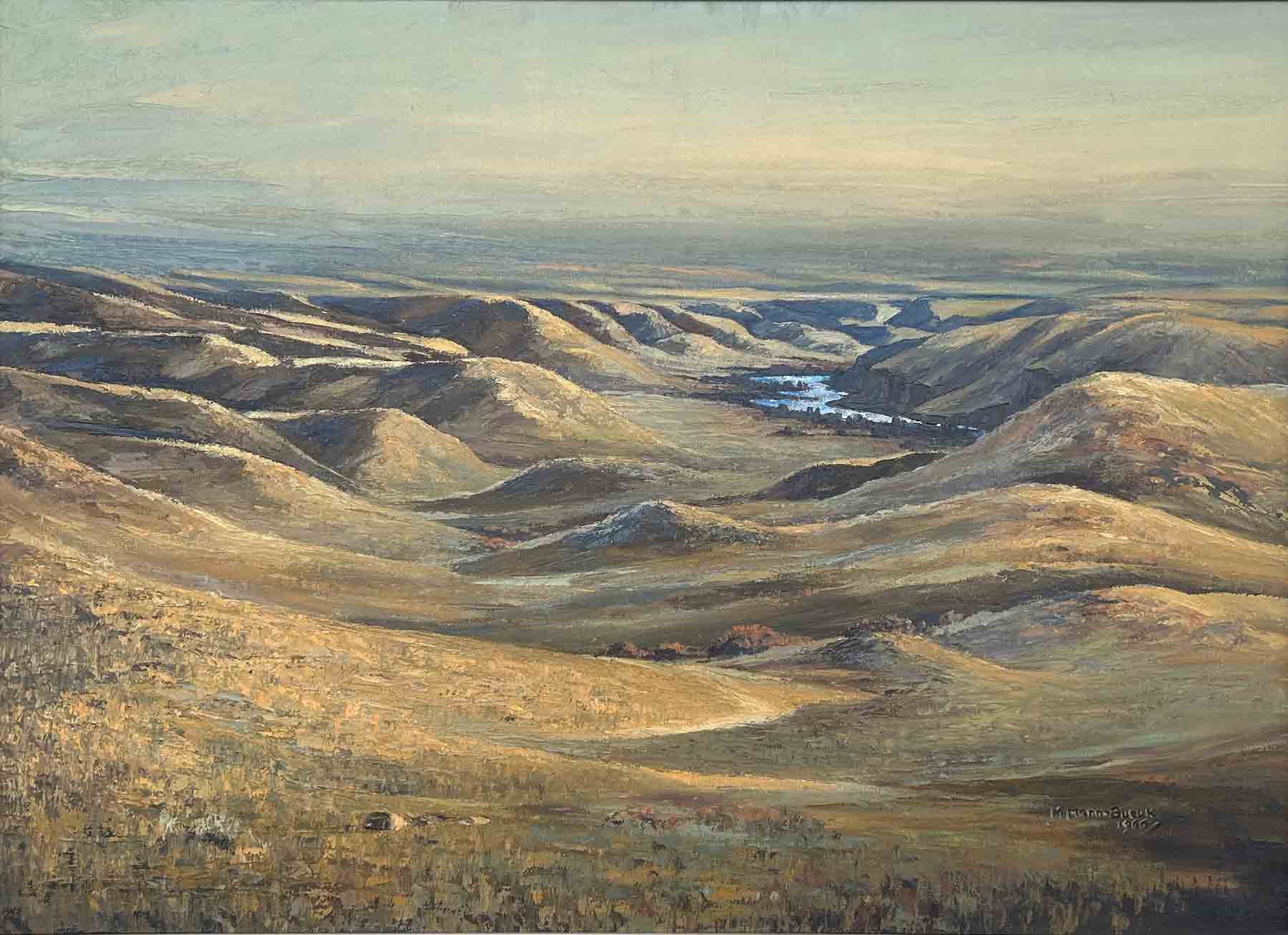

Painted in 1966 by Margaret Mann-Butuk, Light for the Valleys captures the quiet scale and shifting light of the prairie landscape she returned to again and again. Found decades later at a church rummage sale, the painting carries both a documented exhibition history and a deeply personal connection to place.

I’m drawn to this small painting because it feels quietly certain of itself. Old Home was painted in 1980 by Bernice Trider, an artist deeply rooted in Alberta’s Peace Country. It’s modest in scale, carefully made, and clearly loved—one of those works that carries a lifetime of looking, returning, and remembering. Finding it felt less like a discovery and more like being trusted with something that mattered.

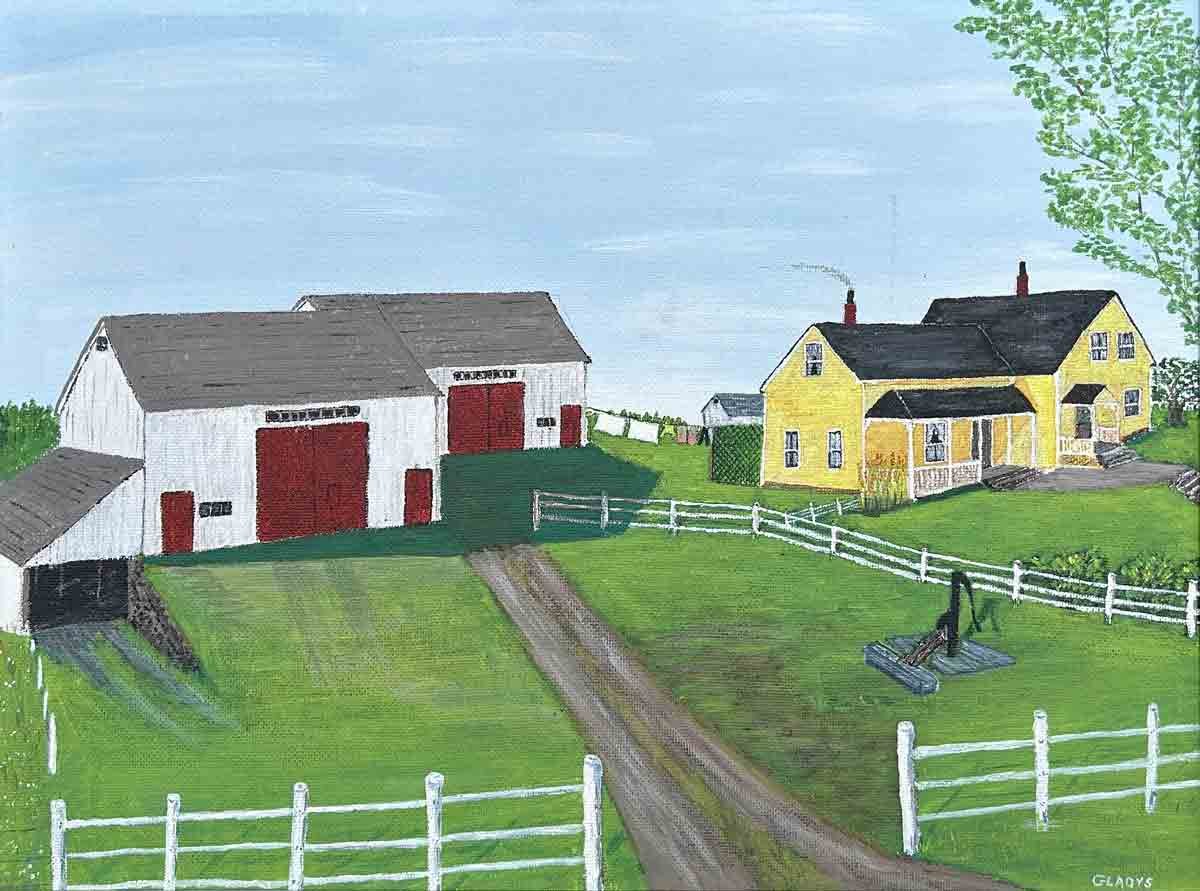

Painted in 1984, My Nova Scotia Home feels like a letter to a place. Gladys Ada Steeves names the location, the date, and the memory directly on the canvas, anchoring the work in a lived relationship with Central Caribou, Nova Scotia.

A small, unsigned-in-every-way-but-name landscape by E. MacLeod. A lake, distant hills, and a restrained palette that rewards slow looking.

A small Alberta landscape, dated June 9, 1968. A name, a place, and a painting that endured.

Painted as a demonstration in 1970, this view of Medicine Lake captures a moment of teaching as much as a place. A working painting, made to be shared.

A winter sugar shack, a thawing stream, and a painter whose story survives only through the work itself. Sugar Shack is a reminder that not all meaningful art leaves a paper trail.

This series of monochromatic paintings by Anton Kohalyk captures the Peace Country not as spectacle, but as something lived in and returned to—winter after winter. Birch stands, frozen sloughs, moonlit clearings, and soft animal movement emerge through restrained colour and confident palette-knife strokes. These are not photographs of the land, but remembered encounters with it.

A prairie field, a solitary figure, and the last stook standing. Signed by Mary Siebert, this painting holds a quiet record of work, place, and passing time.

Painted after a 19th-century lithograph, this mid-century winter scene reflects how images lived on through practice, not preservation.

A signed and dated winter landscape by Augustine C. Frey, painted in Josephburg—but imagining mountains far beyond it. A reminder that landscapes often map memory, not geography.

This is another artwork I found at a thrift store last month. I love it, but I can’t find any information about the artist (signature looks like H.D. Carrigan?). Depicts a street scene of an active alleyway, with the Hotel MacDonald (Edmonton) in background. I love the popcorn vendor!

Found this at a thrift store, and it’s signed Margaret Thomson. Could it be by famous artist Tom Thomson’s sister Margaret?

Found this beautiful landscape by Father Paul-Emile Côté (1913-2014), Canadian artist. Did some research and his medium was shoe polish! His palette included 90 different colors of shoe polish and cream from 20 different brands.

COMMUNICATION

As a graphic and digital designer, I bring this same attentiveness to how people encounter information, space, and storytelling. My professional work focuses on creating clear, considered visual systems that support understanding and engagement—whether through environmental graphics, exhibitions, digital platforms, or print.

I see design as a form of translation: shaping complex ideas into accessible, human-centered experiences while respecting the integrity of the content.

These pieces are ‘decorative’ antiques that I have collaged and painted directly onto, re-contextualizing the pieces and giving them a new story.